- Noah Jacobs Blog

- Posts

- On Curiosity

On Curiosity

What a Catholic Wedding taught me about the risks of over reliance on technology.

2025.06.29

CVI

[Asimov’s Warning, A Silent Priest, Tech’s Boon, Cone of Increasing Dependency, Antikythera Mechanism, Childlike Curiosity]

Thesis: Continuing to ask how the world works, even when technology makes you think you don't have to, is critical to reducing the risks of technological progress.

NOTE: This post is heavily influenced by Jonathan Blow’s speech on preventing the collapse of civilization.

[Asimov’s Warning]

One of the biggest super powers of our species is curiosity.

By asking why and why not and how, we have built wonders of the world. Planes that move faster than sound, power plants that recreate the reactions of the stars, a global system of computers that rivals our own intelligence.

This curiosity serves as a double edged sword, though: the same curiosity that makes us so powerful also gives us the trappings of comfort that leads to complacency.

Isaac Asimov, one of the most clairvoyant & prolific science fiction writers of the 20th century, had a keen understanding of this trade off… he wrote of societies that fell into decadence as soon as they had robots to tend to their every need, or others that grew so haughty in their military might & security that their world decayed around them, or others that continued to optimize for comfort and ended up with men & women afraid of the sunlight & living like grubs in secure steel caves.

While the concept sounds farfetched, it is not—it is a very real pattern of allowing our technological comfort to rob us of the very same drive and curiosity that created it.

Already, we are seeing evidence of frequent LLM use reducing cognitive connectivity*… but the issue is far deeper than just knowledge work.

This does not mean that we should halt technological advancement by any means. We should continue. It simply means that we should never stop asking why, even when we are inclined to take something for granted.

Creation without a mechanism for destruction is a cancer.

Curiosity is the tool that helps keep the door to healthy destruction open.

[A Silent Priest]

I was at a beautiful Catholic wedding service this weekend.

When the Priest went to give his homily, though, he had technical difficulties with the microphone—it kept going in and out and made it difficult enough to understand him that he joked about someone in the audience having a “jammer.”

He was a very good public speaker & could clearly project when he needed to. And, the Church was very obviously designed with the intention of amplifying the voice of the speaker at the Altar, as most Churches are. In other words, if he would have taken the mic off, we likely would have been able to hear him better than we could with the malfunctioning mic.

But, for whatever reason, he didn’t seem to consider that possibility; he more or less took the mic for granted. And, why wouldn’t he? He’s likely used it in every Mass he’s ever done at that Church, just as his predecessor did.

There are a number of internal dialogues that could have gotten him to take off the mic and just use his own voice. One such example:

"Why do I need to wear a microphone? Oh, so everyone can hear me. Well, if I just talk loud enough, they can hear me anyways! I will talk loudly without the mic."

When technology is taken for granted, the issue becomes less of “What am I trying to achieve & how can I get there?” and more of “Why is the technology not working?” This second question is not as important as the first. Still, it is dangerously easy to forget the first question altogether.

[Tech’s Boon]

If the Priest can speak without the microphone, why have one at all?

Well, there are a lot of good reasons:

Someone who is, unlike a Priest, not a professional speaker might need to speak and would greatly benefit from using the microphone

The Priest might have a sore throat one day

The Mass might need to be recorded with good audio, which having a microphone makes very easy

More generally, a microphone and speaker system helps the average person perform better at public speaking than they would without it. These benefits very likely outweigh the calculable cost of buying, maintaining, and running the sound system.

The hidden costs, though, are a bit more interesting:

An exceptional public speaker who does not need a microphone will become more dependent on one by virtue of never having occasion to not use the microphone.

Someone who could learn to publicly speak without a microphone will not have occasion to.

In this way, while we are raising the average, we are also unnecessarily defaulting to a handicap for the top or promising performers.

This does not mean that we need to get rid of microphones at Churches; rather, it means that we need to have a culture that is conscious of it's dependency on technology and always asking 'why' we have something in the first place.

That way, even when technology, on average, enables us, we can simply not use it when we don’t need to.

[Cone of Increasing Dependency]

Forgetting how to do a very human task like public speaking poses minimal risk to society, as it is natural for us to learn it. What is more risky is when we forget how to do artificial tasks that we still depend on.

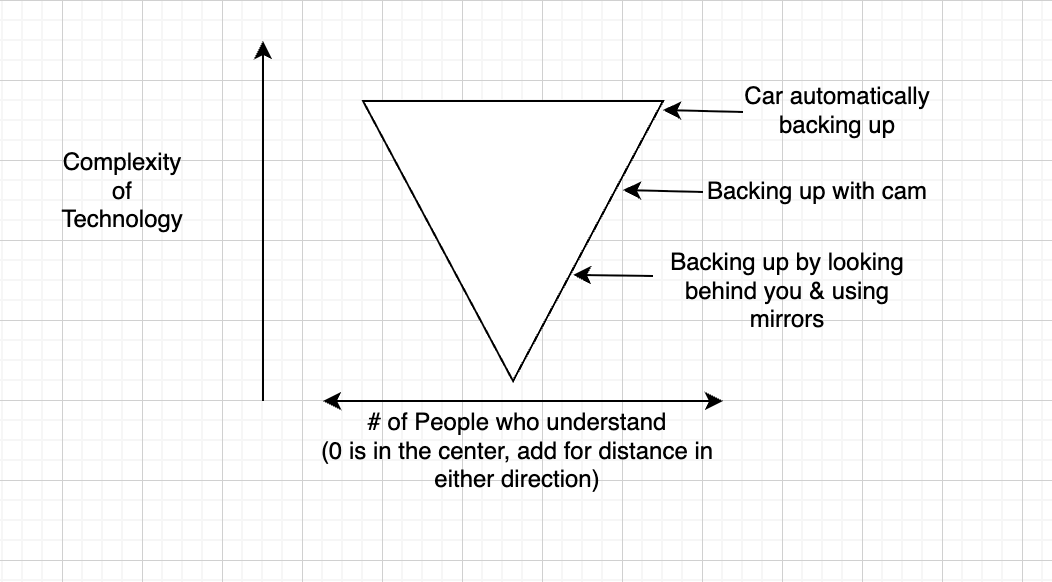

This creates a cone of dependency with an increasingly concentrated failure point.

I am convinced that I am a worse driver by virtue of using a backup camera. I am also convinced that as backup cameras continue to become more and more common, everyone will be worse at driving—at least the backing up part.

This is different than public speaking because 'driving' is learning how to operate an entirely man made artifact. There is nothing inherent in humans about being able to drive cars.

On the other hand, as long as cars keep improving, not knowing how to back up might be fine. We might not even have to know how to do anything to drive in 15 years, let alone backup!

While needing to know how to backup is skill that might be "obsolesced", it is still a rung that exists on the ladder to autonomous vehicles. This means our knowledge about backing up will be encoded into those vehicles... just like our knowledge about manual gear shifting was encoded into systems that enable automatic shifting.

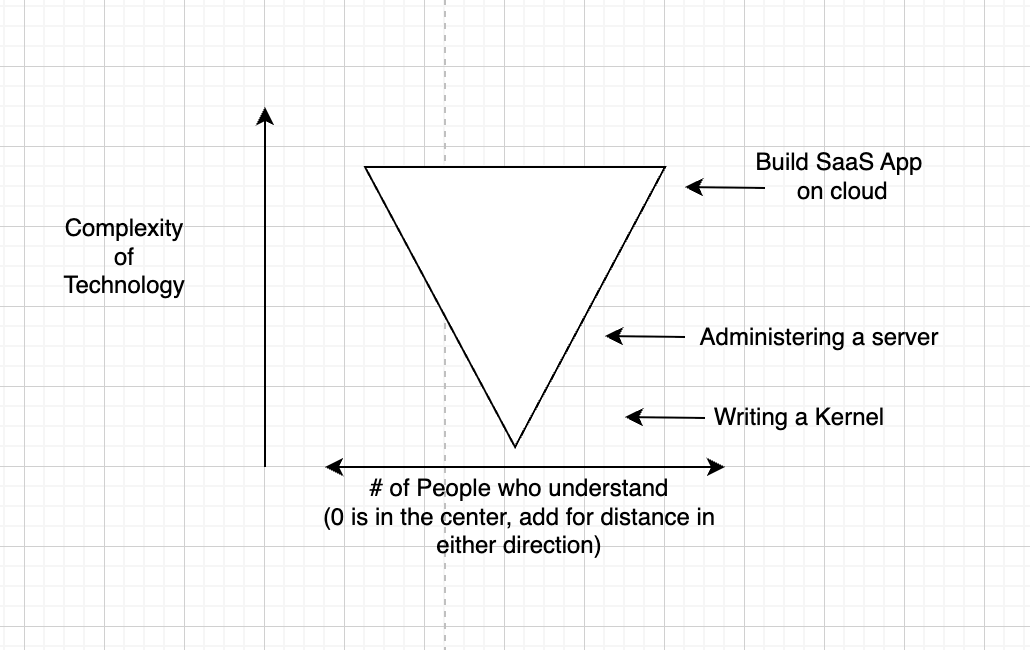

As we increase the complexity of the technology, more people know how to do the most complex thing, but many fewer understand what underlies it; everyone will know how to use self driving cars.

This collective dependency on an increasingly concentrated failure point is a risky thing. And if you don’t see why, just remember how an error at google took down a good chunk of the internet 2 weeks ago or recall the crowd strike outage from last year, which now has its own wikipedia page.

How many people do you think would know how to set up their own server off the cloud or write security in the kernel to replace what Google & Crowdstrike had?

Uh, oh! We’re REALLY top heavy in software…

Certainly far fewer people than the number of people who depend on them!

As we continue going forward, the technology we depend on vs the number of people who understand it is like a cone - the deepest dependencies are what the fewest people understand.

This creates risk because of a deep dependency at the level with the least attention. We mitigate this risk by destroying some of the complexity as we create more, rather than building complexity on top of unneeded complexity.

But this is very hard to do, because what complexity is actually unneeded?

[Antikythera Mechanism]

If you think it’s not that deep & forward progress is guaranteed and we are at the end of history… well, the Greeks may have thought that, too.

The Ancient Greeks had an analog computer, the Antikythera Mechanism, built between 200BC and 100BC. The gears went into it were so complex that, before we found the machine in the 1900s, we thought that such technology was not possible until the 14th century AD.

If someone could build one of these computers with the gears available to him or her, and the knowledge to build the gears was lost, so to would the knowledge to build the computer be lost. If someone knew how to build the computer given the gears, it wouldn’t matter if they couldn’t figure out how to build the gears…

In other words, the technological advancements that we have made are NOT ours to keep. They're ours to lose, just like our ability to speak well in public.

The rusted bits of the Antikythera Mechanism. Wikimedia commons.

Derek J De Solla Price with a recreation of the Antikythera Mechanism. Wikimedia commons.

[Childlike Curiosity]

What is the counterweight to the technical complexity that comes with our rapidly improving capabilities? Is it to stop technological improvement altogether?

I don't think so, not at all. We should keep going!

Rather, we must applying curiosity to everything we build and rely on as much as possible. Take nothing for granted and to go at least one layer deeper than you might naturally be inclined to.

This is especially true when someone tries to sell you new technology, particularly technology that you yourself will be building on. Is all of this complexity and dependency worth the value, or can you achieve the same thing with less?

You don’t want to be dancing on layers of complexity you don’t need to - a lot of the time, you can remove layers between yourself and whatever it is that is below your level.

If you don’t need a microphone to speak, don’t use it.

Live Deeply,